PHYSIOTHERAPEUTIC MANAGEMENT

OVERVIEW OF FROZEN SHOULDER WITH CURRENT CONCEPTS OF PHYSIOTHERAPEUTIC MANAGEMENT

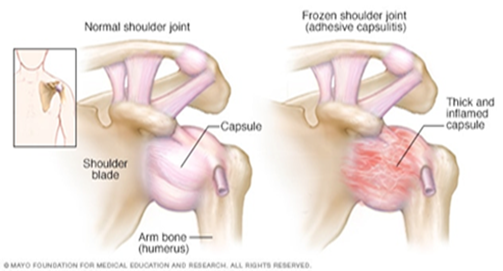

Frozen shoulder, also known as adhesive capsulitis, is defined as “a condition characterized by significant restriction of both active and passive shoulder motion that occurs in the absence of a known shoulder disorder.(1) Patients typically experience insidious shoulder stiffness, severe pain that usually worsens at night, and near-complete loss of passive and active external rotation of the shoulder.(2) It is likely that limitations in range of motion and the pain associated with frozen shoulder are not only related to capsular and ligamentous tightness, but also Fascial restrictions, muscular tightness, and trigger points within the muscles.

Frozen shoulder can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary idiopathic frozen shoulder is often associated with other diseases and conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, and may be the first presentation of a diabetic patient.(3) Patients with systemic diseases such as thyroid diseases(4,5)and Parkinson’s disease(6)are at higher risk.

Secondary adhesive capsulitis can occur after shoulder injuries or immobilization (e.g. rotator cuff tendon tear, Subacromial impingement, biceps tenosynovitis and calcific tendonitis). These patients develop pain from the shoulder pathology, leading to reduced movement in that shoulder and thus developing frozen shoulder.

Frozen shoulder often progresses in three stages:

- Stage 1: Freezing- In the "freezing" stage, you slowly have more and more pain. As the pain worsens, your shoulder loses range of motion. Freezing typically lasts from 6 weeks to 9 months.

- Stage 2: Frozen- Painful symptoms may actually improve during this stage, but the stiffness remains. During the 4 to 6 months of the "frozen" stage, daily activities may be very difficult.(7,8)

- Stage 3: Thawing- Shoulder motion slowly improves during the "thawing" stage as pain begins resolve. Return to normal or close to normal routine daily activities typically takes from 6 months to 2 years.(9,10,11)

Examination

Currently the diagnosis of primary adhesive capsulitis is based on the findings of the patient history and physical examination.(7)

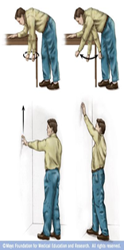

1. Observation of posture and positioning

Eventually, patients with adhesive capsulitis develop adaptive postural deviations such as anterior shoulders or increased thoracic kyphosis as the function of the shoulder complex remains limited and painful, due to lack of capsular extensibility as well as a change in the central nervous system motor patterning due to maladaptive movement.

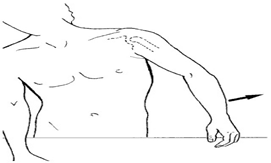

2. Movement pattern

In this condition the glenohumeral joint capsule will adhere to itself and not allow full motion. When this occurs there will be a very evident disturbance in the scapula-humeral rhythm. Any attempts at lifting hand on sideways (abduction) will usually require significant substitution and you will often see a motion like that pictured in the figure below, when an individual attempts abduction.

3. ROM screen: Active/passive/overpressure Range of motions.

Cervical, thoracic, shoulder ROMs with overpressure as well as rib mobility should be evaluated.

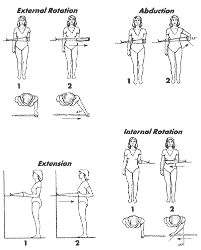

4. Resisted muscle tests -

Shoulder external rotation (ER) / Internal rotation (IR) / abduction (ABd) (seated) should be performed.

Patients with adhesive capsulitis present with weakness in shoulder ER, IR and ABd relative to the asymptomatic side.

5. Function Related Tests

Common issues include :

- Unable to reach above shoulder height (Overhead activities).

- -Unable to throw a ball.

- Unable to quickly reach for something.

- Unable to reach behind your back. E.g.: bra hooking or tucking shirt.

- Unable to reach out to your side and behind. E.g.: reach for seat belt.

- Unable to sleep on your affected side.

PHYSICAL THERAPY INTERVENTIONS

Passive Motion:

Adhesive capsulitis involves fibrotic changes to the capsule-ligamentous structures, continuous passive motion or dynamic splinting are thought to help elongate collagen fibers. Recently, dynamic splinting was also used in patients with Stage 2 (“frozen stage”) adhesive capsulitis and the authors of the study, Gaspar and Willis, noted better outcomes when physical therapy was combined with the Dynasplint® protocol. (17)

Manual Techniques:

Joint mobilization is an effective intervention, several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of joint mobilization in adhesive capsulitis patients.(12,18) In particular, posterior glide and anterior glide mobilization were determined to be more effective for improving external rotation range of motion. In addition, high-grade joint mobilization techniques are more effective than low-grade mobilization in improving glenohumeral mobility and reducing disability of patients with adhesive capsulitis.(19)

As discussed earlier, Myofascial trigger points, focal areas of increased tension within a muscle, may be present in the musculature around the shoulder complex in patients with adhesive capsulitis. The Spray and Stretch® technique for the Subscapularis and Latissimus dorsi muscle may be effective at reducing trigger point irritation, pain, and helping to gradually lengthen tight muscles.

Soft Tissue Mobilization:

Soft tissue mobilization and deep friction massage may benefit. Deep friction massage using the Cyriax method was shown to be superior to superficial heat and diathermy in treatment of patients with adhesive capsulitis. Recently, Instrument-Assisted Soft Tissue Mobilization (IASTM) as Graston Technique®, has become increasingly popular in physical therapy practice. IASTM reportedly provides strong afferent stimulation and reorganization of collagen, as well as in increase in microcirculation.

Therapeutic Exercise:

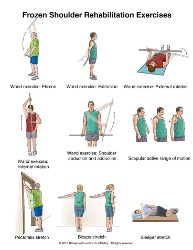

Pain is often most severe during the freezing phase and patients in this phase would benefit from learning pain-relieving techniques. These exercises include gentle shoulder mobilization exercises within the tolerated range (e.g. pendulum exercise, passive supine forward elevation, passive external rotation, and active assisted range of motion in extension, horizontal adduction, and internal rotation). Rotator cuff exercises, as well as posture exercises and exercises for the deltoid and chest also needed. A heat or ice pack can be applied as a modality to relieve pain before starting these exercises. The application of moist heat in conjunction with stretching has been shown to improve muscle extensibility.(19)

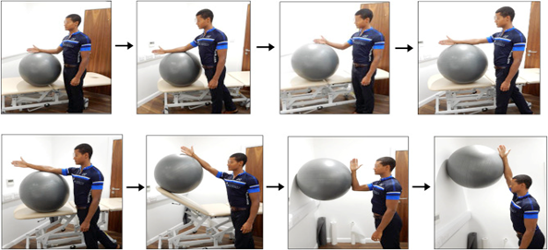

Once range of motion has progressed enough, strengthening to be an appropriate intervention. Strengthening exercises are added to maintain muscle strength. Isometric or static contractions are exercises that require no joint movement and can be done without worrying about increasing pain in the shoulder. Strengthening exercises can also progress from isometric or static contractions, Theraband exercises and Swiss ball and eventually to free weights or weight machines.

The rationale for using modalities in patients includes pain relief and affecting scar tissue (collagen). However, the use of modalities such as Ultra Sound Therapy, Iontophoresis, and Phonophoresis has not been proven to be beneficial in treatment of adhesive capsulitis.(12,13) Interestingly, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) has been shown to significantly reducing pain. Recently, research also suggests that low-power laser therapy and deep heating through diathermy combined with stretching were shown to be more effective than superficial heating for treating frozen shoulder patients. (14,15,16)

In conclusion, this is a challenging condition for both the physical therapist and patient. It is important to make an accurate diagnosis and assessment in order to choose their best interventions. By understanding the published evidence related to the rehabilitation of patients with adhesive capsulitis, both therapists and patients will get benefit with an integrated, multi-faceted, evidence-based approach or interventions.

Modalities:

The rationale for using modalities in patients includes pain relief and affecting scar tissue (collagen). However, the use of modalities such as Ultra Sound Therapy, Iontophoresis, and Phonophoresis has not been proven to be beneficial in treatment of adhesive capsulitis.(12,13) Interestingly, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) has been shown to significantly reducing pain. Recently, research also suggests that low-power laser therapy and deep heating through diathermy combined with stretching were shown to be more effective than superficial heating for treating frozen shoulder patients. (14,15,16)

In conclusion, this is a challenging condition for both the physical therapist and patient. It is important to make an accurate diagnosis and assessment in order to choose their best interventions. By understanding the published evidence related to the rehabilitation of patients with adhesive capsulitis, both therapists and patients will get benefit with an integrated, multi-faceted, evidence-based approach or interventions.

References

- Zuckerman JD, Rokito A. Frozen shoulder: a consensus definition. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:322–5. [PubMed]

- Brue S, Valentin A, Forssblad M, Werner S, Mikkelsen C, Cerulli G. Idiopathic adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: a review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1048–54.

- Pal B, Anderson J, Dick WC, Griffiths ID. Limitation of joint mobility and shoulder capsulitis in insulin- and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Br J Rheumatol. 1986;25:147–51.

- Cakir M, Samanci N, Balci N, Balci MK. Musculoskeletal manifestations in patients with thyroid disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;59:162–7. [PubMed]

- Wohlgethan JR. Frozen shoulder in hyperthyroidism. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:936–9.

- Riley D, Lang AE, Blair RD, Birnbaum A, Reid B. Frozen shoulder and other shoulder disturbances in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:63–6. [PMC free article]

- restgaard TA. Frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis) [Accessed November 1, 2017];UpToDate [online] Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/frozen-shoulder-adhesive-capsulitis .

- Dias R, Cutts S, Massoud S. Frozen shoulder. BMJ. 2005;331:1453–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maund E, Craig D, Suekarran S, et al. Management of frozen shoulder: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16:1–264. [PMC free article]

- Hand C, Clipsham K, Rees JL, Carr AJ. Long-term outcome of frozen shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:231–6.

- Vastamäki H, Kettunen J, Vastamäki M. The natural history of idiopathic frozen shoulder: a 2- to 27-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1133–43. [PMC free article]

- Jewell D. V., Riddle D. L., Thacker L. R. Interventions associated with an increased or decreased likelihood of pain reduction and improved function in patients with adhesive capsulitis: a retrospective cohort study. Phys Ther. 2009;89: 419–429 [PubMed]

- Miller M. D., Wirth M. A., Rockwood C. A., Jr. Thawing the frozen shoulder: the “patient” patient. Orthopedics. 1996; 19:849–853 [PubMed]

- Green S., Buchbinder R., Hetrick S. Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;CD004258, doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004258. [PubMed]

- Stergioulas A. Low-power laser treatment in patients with frozen shoulder: preliminary results. Photomed Laser Surg. 2008; 26:99–105 [PubMed]

- Leung M. S., Cheing G. L. Effects of deep and superficial heating in the management of frozen shoulder. J Rehabil Med. 2008; 40:145–150 [PubMed]

- Gaspar P. D., Willis F. B. Adhesive capsulitis and dynamic splinting: a controlled, cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:111. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson A. J., Godges J. J., Zimmerman G. J., Ounanian L. L. The effect of anterior versus posterior glide joint mobilization on external rotation range of motion in patients with shoulder adhesive capsulitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007; 37:88–99 [PubMed]

- Vermeulen H. M., Rozing P. M., Obermann W. R., le Cessie S., Vliet Vlieland T. P. Comparison of high-grade and low-grade mobilization techniques in the management of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2006; 86:355–368

- Gerwin R. D. Myofascial pain syndromes in the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 1997; 10:130–136 [PubMed]

DR. SHIVANI MANPURE (PT)

SPECTRUM PHYSIO, KAGGADASPURA

SPECTRUM PHYSIO, KAGGADASPURA